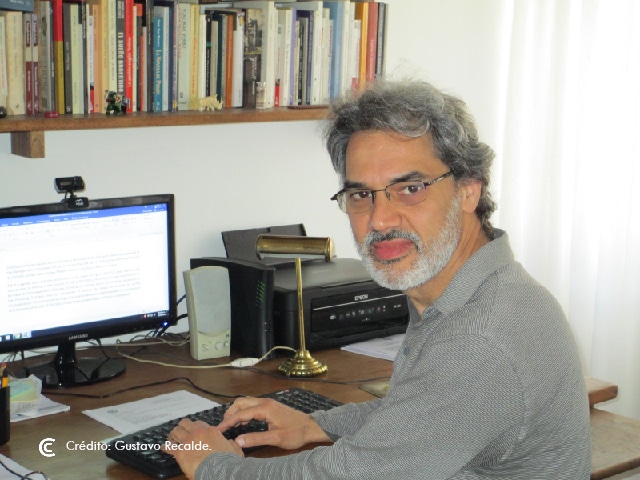

How does journalistic translation work in a period of crisis for the sector? Cultures Connection discussed the issue with the Argentinian translator Gustavo Recalde, who has worked on the adaptation of articles into Spanish for Le Monde Diplomatique Cono Sur since 2002.

The current economic crisis within the media sector is universally recognised, but less well known are the consequences that this has had for every newspaper company. Significant staff cutbacks, delayed or failed salary payments, less coverage of activities, a lack of originality and quality in output, remaining staff overloaded with work. The same scenes repeat themselves in newsrooms and studios regardless of the company or country. Journalistic translation, already neglected from the previous crisis, has almost become a rarity.

International media companies or those that work mostly with international documents have the luxury of having specialists to adapt its content into different languages, guaranteed above all by economic performance or the political demands of the markets they aspire to reach. On the other hand, journalists that have mastered a foreign language are often put in charge of translations, without the training or the necessary rigour.

“Translations for newspapers, in general, are very poorly paid and it is very time-consuming work. Official translations are better paid but are dependent on the amount of business in a country”, Gustavo Recalde explains (Buenos Aires; 1967), sworn translator, national speaker and graduate in Communication.

Recalde knows what he’s talking about, he managed to combine his love for languages, his passion for reading newspaper articles and his ease of writing, and for many years has been working as a French-Spanish translator in print media. He is a contributor to Nueva Sociedad and Review magazines but perhaps his most recognised work is in Le Monde Diplomatique Cono Sur, a South American version of the iconic French newspaper, which has the unique feature of having to fill 75% of its pages with articles from the central magazine and has about 10 freelance translators to do so.

Nowadays, Recalde does not dedicate himself exclusively to translation of print media, he also supplements this work with public translations, dictation of Locution classes and other content creation projects for radio. “I feel more like a communicator,” he explains.

– What differences are there between translation of mass media compared to other sectors?

– The main difference is that media translations are intended for widespread distribution. They must be accurate, but dynamic and easy to read. The translator must ensure that the text is easily read, because when the reader has to make an effort to understand a careless translation, he will probably give up on it.

– Making Le Monde Cono Sur is a long and meticulous process of producing dossiers that perhaps makes it different from the average news sources in Argentina. Could you explain what your work is like from the moment you are offered a translation until the story is published?

– The articles arrive from the French edition, which means the first thing to do is to read and edit the original article in French sent by the authors. Once the articles are received in Argentina, the editors and publishers are in charge of distributing them to the translators. The translator receives the article by email, and, in general has 48 hours to translate it. Sometimes, according to their length and the journal deadline time pressures, the article could be delivered one day to be done for the next. Once the translation has been finished and sent, the editor is responsible for the editing process of the article translated into Spanish: the adapting of titles, leads and writing summaries. He also checks that there are no translation problems, so he has to know French. Then it is passed on to the proofreader, who is in charge of making the necessary adjustments in terms of spelling corrections, writing and style.

– Once the translation is ready is the work over or do you have to keep track until its publication?

– What I usually do is read my translation once it has been published to know what adjustments they have made to the text that I delivered. Above all those that are related to the writing style. That allows me to integrate new writing resources. I do not always agree with the modifications made, but this is always going to be a part of the work. Equally, there are more modifications that make sense than ones with which I do not agree, so the balance is positive. Luckily, I have never had any complaints or problems regarding my translations. And I’ve been here for 16 years now, which is a good sign.

The translator must ensure that the text is easily read, because when the reader has to make an effort to understand a careless translation, he will probably give up on it.

– What advice do you take into account when it is time to translate an article?

– I try my best to ensure my text is as readable as possible, even if the French original does not particularly flow. Although, of course, I always respect the author’s work. One does not have to sacrifice the content, nor the complexities of the text, in order to make it lucid.

– What are the specific problems for translation designed for the media?

– For media translations, there is a lot of pressure on submitting them on time, making my reviewing time significantly shorter; there is no time to leave the work and look at it again another time with a fresh perspective. It’s to be expected with newspapers. There is not really another option when it comes to ‘due dates’, as the news piece or opinion column will rapidly lose relevance. Equally this often happens with other less urgent types of translation as they get left to the last minute, the translator having underestimated the amount of work and the time needed to produce a good translation.

– With Le Monde Cono Sur, French translations of articles that are produced in Argentina are also shared and used in other Spanish-speaking countries where the newspaper exists. Do you take into account all these readers with so many cultural and linguistic differences?

– Yes, I try to avoid localisms; the use of ‘voseo’, for example. Also, the editors of the other Spanish editions who receive our translations make adjustments to their Spanish spoken in their country where they see fit, particularly the mainland Spanish edition.

For media translations, there is a lot of pressure on submitting them on time, making my reviewing time significantly shorter; there is no time to leave the work and look at it again another time with a fresh perspective.

– Do journalists have guidelines of esthetic or technical requirements for the translators?

– I had numerous meetings with the editor when I first started and, in these meetings, I would receive the necessary advice. For example, I was told to avoid localisms or expressions clearly from Rio de la Plata or avoiding the use of the present historic, which is very common in French, when adapting tenses. After this, with only a few general corrections that the author or editor could send via email, as well as some experience of having worked in the media sector and being an avid reader of newspaper articles myself, I haven’t had many other big problems when translating. Of course, there are articles that can be particularly tricky, but that just means they take more time.

– What makes those articles difficult?

– They are often articles that require a lot of significant research into their themes, or have very technical content. But also there are some that require more reformulation due to it being almost impossible to find a phrase in Spanish that reflects the character and sense of the original text. It’s not just about making the content understandable; one has to ensure the reader can immerse themselves naturally in the article without having to consider the words too much.

– Do the translator’s rights belong to the newspaper?

– They belong to the newspaper, yes. The topic of intellectual rights interested me when I saw my translations in various forms, but it’s a lost battle. For the time being, monitoring your translations, so they are not copied online, is impossible. I try to fight so they pay good rates in order to compensate for this uncontrollable diffusion of my work. There are few editorials that look after their translators.

– What is your work routine like?

– When I receive the article, I do a first quick scan of the content to get an idea of the themes and its complexities, and I work out how much time I need. I then carry on with the help of bilingual and monolingual dictionaries and pages or articles related to the theme. The current development of the Internet helps speed things up enormously, allowing one to research as they translate. I’m the type that enjoys writing numerous options for phrases or words and after a second or third reading I choose the final version. I do the first, second and third readings of my translation whilst meticulously following the original. For the final reading, just before I submit, I do not look at the original again but instead try to spend time, after translating, reviewing my work with fresh eyes that are detached from the original text. This is certainly the most pleasant stage in the process.

Immediacy and the reduction of costs always win over quality. But this is also a problem you can find in articles in general, not just translations.

– Do you follow translations on various media platforms?

– I read translated books and articles, yes.

– What kind of level of translation do you find?

– I annoys me greatly when I find texts that are incomprehensible due to a bad or careless translation. There are still good translators out there but, due to the fact that companies pay poorly, searching for the ‘cheapest’ way above all else, the profession of a translator continues to be undermined and there are less and less professionals who dedicate themselves to translating in a serious way, making a living from this profession.

– Is the media interested in offering good translations?

– It depends. Generally, the media forms that work with translated texts take more time to edit and revise them, taking greater care and demanding high quality from their translators. In newspaper translations, for example, I see a lot of carelessness, numerous translation errors. Sadly, nowadays, the phenomenons of teleworking and offshoring prioritise cost over quality. Immediacy and the reduction of costs always win over quality in these cases. But this is also a problem you can find in articles in general, not just translations. It can be very demoralising for a translator, often causing one to leave and go looking for other working opportunities. It may sound pessimistic but I will often joke and say “in my next life I am definitely not going to be translator”.

– Can a translator also be considered a journalist in some way?

– In translations involved with graphic media for large-scale diffusion, unknowingly, one sometimes ends up editing articles themselves; it’s a form of journalistic work.

Translation into English: Madeleine Hancock and William Steel

Discover our translation services.