The difficulty of “interpreting” a language and translating it can have unpleasant consequences in the world of politics or international conflicts.

A recent translation error at the EU, reported by the magazine Les Inrockuptibles, reminds us of the difficulty of “interpreting” a language and translating it, and of the unpleasant consequences that this can have in the world of politics or international conflicts.

We know about erroneous interpretations of biblical texts, the lack of attention in the translation of some novels; French letter instead of condom (French letter)]; “fly ripped apart” instead of an open fly (an open fly), to continue on the same path – but we know less about mistakes made by translators working for international organizations or in intergovernmental negotiations, which sometimes have unfortunate consequences on the sequence of events.

In the case described by the Inrockuptibles, there was a vote on 10 December 2013 on the report prepared by a Portuguese representative on a project to make abortion “a European right”. The interpreting error from Portuguese to French and to German centered on the word “rejeitar” which was translated as “support” instead of “vote against”. “For practical reasons, the European Union decided to appoint five main interpreters: English, French, Spanish, German and Italian. They served as references to others, whose translations were staggered. As a result, all the interpreters from the French and German channels were misled, repeating the misinterpretation in turn. The Romanian and Bulgarian representatives were for example some of the victims as a result of the ricochet”, the journalist Basile Lemaire explains in more detail.

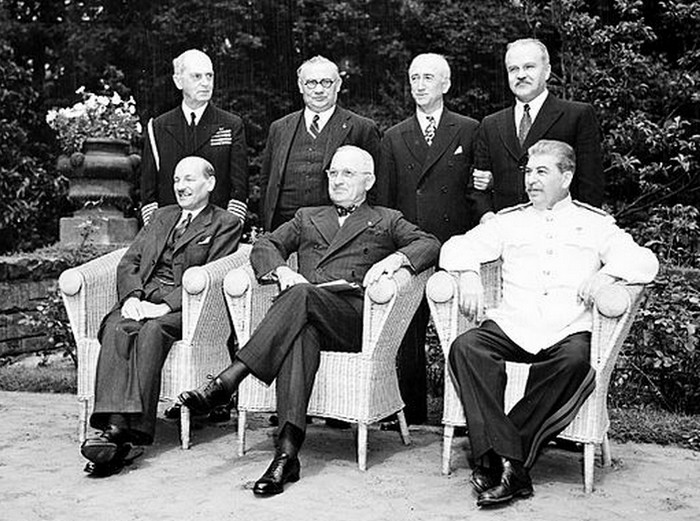

Among the historical interpreting errors that relate to international conflicts, one of the best-known is the unconditional surrender of Japan. The professor Jean Delisle of the University of Ottawa suggests in his work: “In his book The Fall of Japan, William Craig writes that on the issue of the Potsdam Conference, in July 1945, the Allies sent an ultimatum to the Japanese Prime Minister. They demanded the unconditional surrender of the Japan. In Tokyo, journalists urged the Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki to communicate the response to the authorities. He replied that his Government ‘refrained from any comment at the moment’. In his declaration, he used the word mokusatsu, which is very ambiguous. The Japanese news agencies and translators give it the sense of ‘to treat with silent contempt’, ‘to not even take into account’ (to ignore), which in essence meant to the Prime Minister: ‘We categorically reject your ultimatum’. Americans saw this as a complete dismissal. Ten days later, they dropped their deadly bomb on the Japanese city”.

More recently, a translation error extended the war in Georgia by a month. Interviewed in 2008 about the reasons for not respecting the ceasefire agreement by the Russians in which France played the role of negotiator, Bernard Kouchner, then the Minister of Foreign Affairs, explained, very simply that a translation error had been made in the Russian version of the agreement…

From there to conclude that translators only have a historic role when they are wrong…

Translation into English: Chloe Findlay

Discover our translation agency.