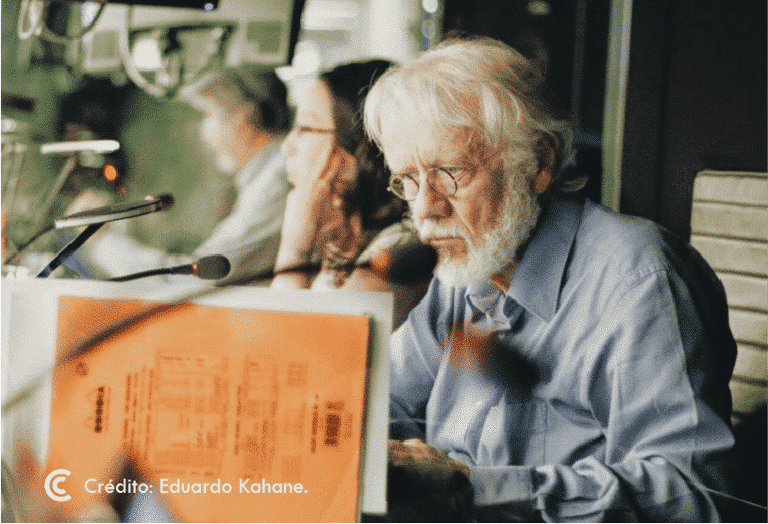

Left defenceless, facing persecution and death. Eduardo Kahane, member of the International Association of Conference Interpreters, recently spoke to Cultures Connection, explaining the difficulties interpreters have when working in zones of conflict.

“I think my life ended back then”, he bravely comments for the documentary ‘The Interpreters’.

An interpreter who has worked for the US military forces during the war with Afghanistan and had to escape to Greece, closely avoiding capture by the Taliban. And he is one of the lucky ones. He did not have permission for asylum in Europe, nor protection from the United States government after his troops abandoned Asian territory, but many of his colleagues in the same situation were not even able to escape the country, spending days in hiding and regularly risking death.

This is how many interpreters in zones of conflict live, something to which Eduardo Kahane, Interpreter and member of the International Association of Conference Interpreters (IACI) since 1973, can attest. Kahane participates in a Commission that works to improve working conditions and safety for workers in conflict zones. The working group was formed in 2008 largely due to some critical articles, written by the Association, which informed readers about the alarming lack of protection these interpreters faced.

Currently, the IACI, alongside the International Federation of Translators, Red T, Critical Link International and the Worldwide Association for Sign Language Interpreters, are looking to achieve international recognition for this work. In 2010, they gained approval from the Council of Europe on a decision that pressed for the protection of interpreters in zones of conflict, and now they want the United Nations to do the same.

– Did the Association not work to resolve these difficulties before?

– We did not view the situation as problematic before because the problems of conflict were simply not as serious; the issue first came to light in 2007 when the Taliban started kidnapping journalists. I flagged the issue to the Association around the time when they took the Italian journalist from La Repubblica, Daniele Mastrogiacomo, and that invoked a very important public movement for his release which was driven by the journalism community. Having observed how these journalists took to the streets for not only their colleague, but for the interpreter and driver that accompanied him and had been kidnapped too, I saw that our Association was not in any way sufficiently aware of the danger and abuse these interpreters face. This situation was not recognised by society as a whole at all; it was the journalists who brought this vital issue to light.

– What are the most serious problems that interpreters in zones of conflicts face?

– They find themselves in a complicated situation because, when they attend a meeting between two of the opposing sides, one of the parties will simply identify the interpreter as part of the group that have hired them. Neither their work, nor them as an individual, is recognised as being neutral. Generally, they are not qualified interpreters, despite their knowledge of languages; they live in areas where professional training does not exist. They might only be university students or taxi drivers, but they are able to fulfill a societal function that is indispensable in the given place and moment. There are lots of other problems too. For example, whether interpreters ought to know how to defend themselves, in case they are attacked, or what about if they are with an American or European military group and are going to have to work with civilians, they will have to decide whether to wear a uniform or not, weighing up the risk of it turning them into a more easily identifiable target. All these factors contribute to them being viewed as the ‘enemy side’. Equally, there are difficult situations to do with the communities themselves. For example, the Taliban in Afghanistan do not even want to be seen by the Western world, and they will therefore reject any type of communication that opens them up to another culture.

We did not view the situation as problematic before because the problems of conflict were simply not as serious; the issue first came to light in 2007 when the Taliban started kidnapping journalists

– Why do local groups, like the example you used of the Taliban, view interpreters as the enemy? Does it have to do with not knowing the profession or due to the situation they work in?

– They do not understand the concept of an interpreter, what they do and how the job works, it is something very foreign for them. They see someone who is acting as an intermediary and who has come as part of a group, and therefore must share in that group’s opinions. And so, they will automatically identify them as an opponent too, no questions asked. What’s more, as soon as they begin to identify the interpreter as an enemy, their family is viewed in that way too. An interpreter’s place in the community soon becomes untenable. When the groups go on assigned missions, they are left as outcasts in the zones of conflict where they worked and, of course, exposed to all kinds of potential violence from someone who may be looking to take revenge, despite them being in no way responsible for the situation.

– Is there some sort of record of interpreters who have been killed or injured in the field?

– No, this is something that we have been demanding for years. You have to really search and be persistent to find these figures as, more often than not, the data belongs to militaries or social organisations and is not published. Also, often when interpreters stay in the place where they work, there is no follow up on what’s happened to them. We don’t have any figures but these are highly important as there are many interpreters who have gone missing, have been killed or have families in very difficult circumstances. If we ever did receive these records, the results would certainly be shocking.

– Another problem that you mentioned is the hiring modalities for interpreters. Why is that?

– An interpreter finds his or herself subject to the conditions offered by international organisations, humanitarian institutions and media outlets. He or she never knows how much they are going to be paid nor the potential danger they may face when hired as, often, they do not know the real objective of their missions. After learning more about this, the IACI, Red T and the International Federation of Translators formed a coalition of NGOs and wrote a field guide with a series of recommendations for interpreters who are hired, with the aim that at least there are some rules which provide some acceptable working conditions, although, of course, they can be highly precarious.

When they attend a meeting between two of the opposing sides, one of the parties will simply identify the interpreter as part of the group that have hired them.

– Is there not international legislation protecting them?

– There is not even recognition for the interpreting profession, which is a struggle for interpreters across the world, not just in zones of conflict. The IACI has been trying to achieve title recognition from United Nations organisations for years and, so far, it has not been possible. We work very hard so that people will acknowledge, firstly, the profession in general, and secondly, the need to protect interpreters in the West against claims that make them responsible for problems and susceptible to sanctions, criminalisation or some kind of civil or legal implications. They do not have this type of protection; there is hardly any acknowledgement for the situation of interpreters in zones of conflict. At the moment we have an ongoing petition to the United Nations that needs 50,000 signatures in order to be acknowledged and gain the recognition of interpreters in zones of conflict, as well as demanding their protection.

– You were very critical of how these interpreters go unnoticed by the Association. Do you think that that is due to ignorance or an elitist outlook of the profession?

– I think both of these things are equally responsible. Firstly, there was no information. Secondly, the IACI was formed in a very particular historical context: after World War II, with the Nuremberg trials and the creation of the United Nations. It has always been a profession that is highly determined by its current political and historical context. And when these services start to be demanded in other industries, it is difficult for those who have been practicing the profession in one particular way for forty or fifty years to start adapting to these changes. So, it is not that I was criticising with reference to elitism, although it can be that way sometimes. What we are really trying to do is put a stop to the fact that other contexts, where interpretation services are necessary, go unnoticed. Not only in zones of conflict, but also nowadays we need these services amongst ethnic minorities or groups of immigrants and asylum seekers that arrive at refugee shelters. Society is becoming more conscious and seeking interpretation services for places where there wasn’t before: at police stations, hospitals, reception centres. These new circumstances have to also be recognised by the professionals who have been working exclusively in specific circles until now.

We don’t have any figures but these are highly important as there are many interpreters who have gone missing, have been killed or have families in very difficult circumstances. If we ever did receive these records, the results would certainly be shocking.

– How has the situation changed for interpreters since this heightened awareness?

– We took a leap of faith in 2008. Numerous colleagues, who were not aware of the issues we were raising, were surprised and thought that this transformed awareness would never become a reality due to the fact that it would not involve other forms of interpretation. However, this was not the case; the resolution was approved by an overwhelming majority at the Association. From then on, the matter became part of our acts and publications. A collective effort was made to ensure that the issue would be the subject of negotiation with international organisations given that it is a highly relevant theme to society nowadays, and we still haven’t found a solution. We are talking about a fundamental step shaping the future of our profession as, in reality, it gives rise to new forms of interpretation, such as communication from a distance or the use of new technology, and it is therefore producing a paradigm shift.

– Why do you think that human rights organisations or the United Nations do not feel compelled to put in place initiatives which protect the interpreters who are so often a fundamental part of the work they do?

– When someone mentions the United Nations, they are thinking of a global institution, but the United Nations obeys the wishes of the States. And, yes, the States are not particularly inclined to giving protection to interpreters who have worked in zones of conflict; it makes it difficult for a country’s position on an international level to go against the flow and demand protection for them. When a country proposes something to the UN, it has to have been approved by internal consensus. In each country, how these interpreters are perceived, and whether they should be accepted as an asylum seeker or a protected person, changes from case to case. There are ministries that have a more open, or more restricted, vision than others. By taking this to the UN, we are using the institution as a platform to make all of society aware of the problem.

Translation into English: Madeleine Hancock

Discover our interpretation services.