Today, August 26, is the birthday of the famous Argentine writer Julio Cortázar, and for that reason, we will focus on his translation of Robinson Crusoe.

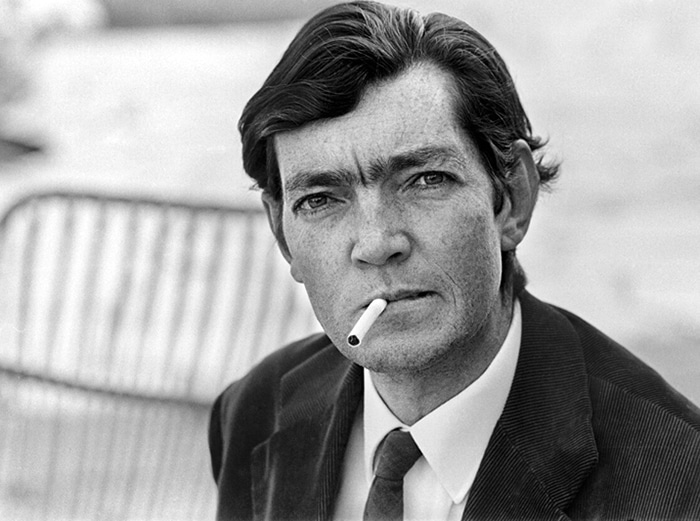

Today, August 26, is the birthday of the great Argentine writer Julio Cortázar (who would now be turning 101). To mark this date, let us take a look at a perhaps less-known aspect of his work, but one which is no less interesting: Julio Cortázar, the translator.

Cortázar: first, translator; then, writer

Julio Cortázar is one of those great writers who, like his countryman Borges started out as a translator before becoming a writer. The author of Rayuela (Hopscotch), one of the most influential Spanish language novels of the twentieth century, confesses that: “I also think that what helped me was learning a foreign language at an early age, and I acknowledge that, from the beginning, I found translation fascinating. If had not been a writer, I would have been a translator. ”

Youth and education

Julio Cortázar was born in Brussels in 1914 to Argentine parents. Cortázar spent his early years in Switzerland and Spain before his family decided to return to Argentina. A frail child, he was often confined to bed for days on end, and read Jules Verne, Rimbaud, Montaigne and Cocteau, among other authors. It was thus natural for him to begin his career as a teacher of literature, later, becoming a professor of French literature before turning increasingly to translation.

Julio Cortázar, translator

Although he had been translating for the French magazine Leoplan since 1937, his first literary translation was Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe in 1945. This was the beginning of a long series of translations, such as, for example, the works of Marguerite Yourcenar (Memoirs of Hadrian, 1955); of G.K. Chesterton; André Gide; or even Marcel Aymé, for instance. In 1948 he qualified as a sworn translator in both English and French and began working for international organizations such as UNESCO and the Atomic Energy Commission.

Cortázar’s translation of Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe was the first literary translation Cortázar undertook. Note that he, like Borges, had no misgivings about tweaking the original text. While Defoe’s work, considered the first novel in the English language, has been subject to numerous mutilations since its publication in 1719, Cortázar’s interventions never cease to amaze: any and all references to the lengthy process experienced by the protagonist of the novel in his passage from atheism to Christianity were completely omitted. Therefore, in the version translated by the Argentine writer, entire pages expounding mystical-religious issues are missing! For example, in the following passage, Cortázar considered it appropriate to publish bluntly:

Defoe’s version

(…) how [the devil] had a secret access to our passions and to our affections, and to adapt his snares to our inclinations, so as to cause us even to be our own tempters, and run upon our destruction by our own choice.

I found it was not so easy to imprint right notions in his mind about the devil as it was about the being of a God. Nature assisted all my arguments to evidence to him even the necessity of a great First Cause, an overruling, governing Power, a secret directing Providence, and of the equity and justice of paying homage to Him that made us, and the like; but there appeared nothing of this kind in the notion of an evil spirit, of his origin, his being, his nature, and above all, of his inclination to do evil, and to draw us in to do so too; and the poor creature puzzled me once in such a manner, by a question merely natural and innocent, that I scarce knew what to say to him. I had been talking a great deal to him of the power of God, His omnipotence, His aversion to sin, His being a consuming fire to the workers of iniquity; how, as He had made us all, He could destroy us and all the world in a moment; and he listened with great seriousness to me all the while. After this I had been telling him how the devil was God’s enemy in the hearts of men, and used all his malice and skill to defeat the good designs of Providence, and to ruin the kingdom of Christ in the world, and the like.

Cortázar’s version

I showed him how the devil has secret access to our passions and affections, and cunningly tends his traps, taking advantage of our inclinations to induce us to tempt ourselves, thus sinking of our own free will into destruction.

I told him how the devil is the enemy of God in the hearts of men and therein employs all his malice and skill to prevent the good designs of Providence, in order to cause the ruin of the kingdom of Christ, when Friday interrupted me.

Discover our translation company.