Storie of translators: fourteen years for a translation, the deadline is a bit long… but if the text in question is that of the Rosetta Stone…

As every translator knows, translation is a glorious task. So what about being the first person to translate a language? This is certainly the best way to get high schools in Grenoble, Dijon, Figeac, Lattes, the University of Albi, and a crater on the moon named after you…

A life dedicated to old things

Does being born to an elderly mother predispose you to a taste for old things? The question arises in the case of Champollion, who was born in 1790 when his mother was 48 years old and who developed a passion for archeology from a very young age. Born in Figeac, he left his hometown in 1801 to meet his brother in Grenoble, then in 1807 he moved to Paris to continue his studies in Latin, ancient Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Chaldean, Persian and Coptic (because taking classes of English or Spanish would have been too simple).

And what if I deciphered hieroglyphics?

It was in 1808 that Champollion had, for the first time, the idea of studying hieroglyphics with the intention of deciphering them. Alexandre Lenoir had just published a decryption of the hieroglyphics, more a whimsical work than a complete one, therefore triggering Jean-François’s curiosity. His curiosity, but also his competitive nature: Etienne Quatremère was working on his Critical and historical research on the Egyptian language…in a way, it was one historic translation agency competing with another.

The various Egyptian scripts (just to make things more complicated)

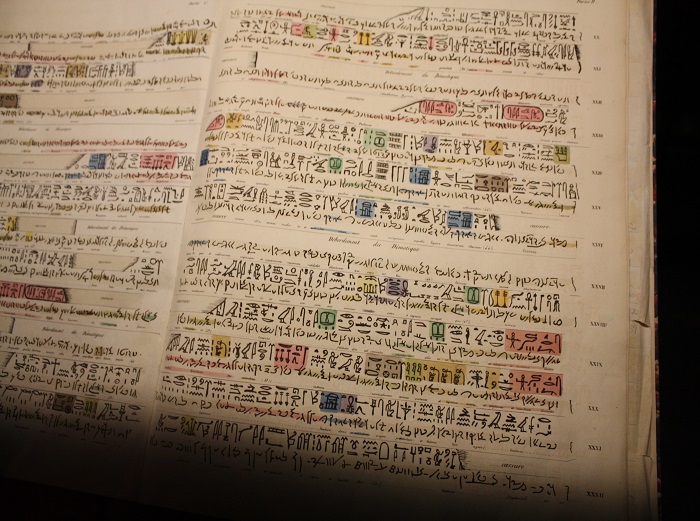

But this was not an easy task. Apart from the different Coptic dialects that he believed are derived from Egyptian, he also had to study three different sign systems: the hieroglyphics, of course, but also the hieratic writings (a cursive form derived from the hieroglyphs) and the demotic writings (an evolution of the hieratic characters intended to make writing even faster).

The Rosetta Stone, my best friend

In 1809 he began studying the Rosetta Stone, this stele engraved under Ptolemy V in 196 BC, which contains a decree in two languages (ancient Greek and ancient Egyptian) and three scripts (hieroglyphics, demotic, and the Greek alphabet). But it was not until 1821 that he decrypted his first royal cartouches. In 1822, he realized that he could decipher Egyptian names: according to the legend, he then would have said, “I’ve got it,” before falling into a coma for several days…

The hieroglyphics, those little rascals

That year, he described the hieroglyphics as “a complex system, a writing system at once figurative, symbolic, and phonetic, in one same text, one same sentence, and I would even say in one same word.” Subsequent generations of Egyptologists distinguished three categories of signs: words-signs (or ideograms designating an object or, by metonymy, an action); phonetic signs (or phonograms, corresponding to one or more consonants); and determiners (indicating the lexical field of a word).

The father of Egyptology

It was in 1824 that Champollion published his Precis of the hieroglyphic system of ancient Egyptians, or the research on the basic elements of those sacred writings, in their various combinations, and the relationship of this system with other Egyptian graphical methods, thereby confirming the creation of a new discipline: Egyptology.

Discover our translation company.